The article appeared in the Sheffield Spectator. It was found by a member of the Group and it’s been re-formatted from its original 4 column format.

A Kind of Hush – Clare Jenkins explores the distant past of a tranquil Sheffield Suburb

A friend recently found herself in Stumperlowe one Saturday, looking for the Soroptomists’ jumble sale. It was an unsettling experience. `”What a weird place.” she whispered nervously next time we met. “Very Stepford Wives…”

Wander round Stumperlowe even on a weekday, with the sun shining, and you can see what she means. Large houses – the semis are substantial, while the detacheds are HUGE – set back from thickly moss-covered pavements, hidden behind laurels and variegated conifers. standing unblinking and remote at the top of neat lawns.

The first thing you notice is that it’s very quiet in this, one of the city’s most ancient districts. There’s muted bird song, the rustling of leaves, the whoosh of the odd squirrel leapfrogging over wrought iron gateposts, plus the purr of the occasional car. But there are very few people. Not on foot. anyway- Why should there be? There are no shops here, no community centre, no bus stops. no church – it’s halfway between St John’s. Ranmoor and Christ Church, Fulwood. Nothing. that is. to walk to. So the inhabitants either stay indoors behind the Austrian blinds, or glide out of their driveway in their indispensable cars.

The first thing you notice is that it’s very quiet in this, one of the city’s most ancient districts. There’s muted bird song, the rustling of leaves, the whoosh of the odd squirrel leapfrogging over wrought iron gateposts, plus the purr of the occasional car. But there are very few people. Not on foot. anyway- Why should there be? There are no shops here, no community centre, no bus stops. no church – it’s halfway between St John’s. Ranmoor and Christ Church, Fulwood. Nothing. that is. to walk to. So the inhabitants either stay indoors behind the Austrian blinds, or glide out of their driveway in their indispensable cars.

In a morning of zig-zagging up and down steep Stumperlowe Streets, the only human beings I saw were three workmen renovating a perfectly decent looking house. a postman, an elderly man raking up leaves in his garden and an elderly woman returning from the postbox. The latter two both said “Good morning” in posh Stumperlowe voices. Presumably their neighbours were inside cloning.

If Stumperlowe is weird, it’s quite possibly as much to do with its distant past as with its isolated present. The name is old English for ‘Stump’s burial ground’. The Stump in question was one of Lord of the Manor Waltheof’s chieftains back in Saxon times. A sort of Stump of the Dig. And historians reckon he’s buried somewhere in the grounds of what is now – and has been since the 16th Century – Stumperlowe Hall.

Waltheof had his own hall here, in the old village of Hallam. It’s certainly an impressive site for a Saxon village, halfway up a hillside looking one way out to Ringinglow and Hallam Moors, another across the valley which now houses the city to Rotherham, a third over to Stannington and Loxley.

Up until the last century, it must have been predominantly rural, boasting just the odd mansion and farmhouse, like Stumperlowe Grange Farm, a slate-roofed low stone building now reduced to a small-holding complete with crowing cockerel. Around it is quite a collection of 1930s angles, 1950s eaves, 1960s boxed flats and the odd oak-beamed rustic refugee from Hamelin.

The Grange itself is very impressive. In 1883, it belonged to W E Layeock, Esq. JP, ex- Mayor of Sheffield. (Stumperlowe has always had more than its fair share of JPs and OBEs. Majors and Colonels. PhDs and, for some reason, haematologists.) Originally owned by General Murray ‘of the lordly Scottish house of Athol’, Colonel of the Black Watch, the Grange passed into the hands of the merchant Wilsons. By Laycock’s time, it was being described in gushing terms: “quite in the country and yet conveniently near to the town. it would be hard to imagine a more desirable place in which to spend the evening of an active and honourable life.” As you wandered around its 50 acres. you could see “the graceful spire of Laughton en le Morthen when the western heavens are aglow with the glories of autumn sunsets.” Neighbouring the Grange is a cluster of old stone houses, one of which, Stumperlowe House, boasts two splendid windows. One is engraved with the Latin Fide Non Minis and Dum Vivo Canebo. Which may or may not translate as ‘I trust not weapons’ and ‘While I live I shall sing’. The other window bears a beautiful red, gold and green stained glass design.

Just across the road, up a long sweeping drive and surrounded on three sides by thick laurel bushes, is Stumperlowe Hall itself, one of the oldest inhabited residences in the city. Although there are references to such a hall in the time of Richard II, this particular house dates back to 1657, and could serve as a model for Manderlay, Daphne Du Maurier’s haunting home of Rebecca.

In Queen Elizabeth I’s time. Robert Mitchell and his two daughters lived in Stumperlowe. The elder, Margaret, married Henry Hall of Edale, and their son Robert built the hall proper. He also became Lord of the Manor of Midhope. Unfortunately, one of his sons, Henry II, dissipated his wealth in the dissolute company of ‘Fox of Fulwood and Bright of Whirlow’. As a result, his widow and children lost the hall in 1716 to an apothecary and lead merchant. Stumperlowe Hall was rebuilt in the 1850s and, in 1947, became the home of the chairman of the Kennings business. It incorporated not only the usual library, drawing room and study but also a ‘sitting room for servants’ and a service cottage and barn, believed to be the oldest buildings in Fulwood.

In the pre-war years, the grand houses were joined by Stumperlowe Mansions, 35 service flats whose brochure talks of them being finished in a ‘quiet, dignified way. Residents had access to a lift and restaurant, while ‘dinner parties are catered for on request’ The flats themselves were furnished with sturdy 1930s chairs, drinks tables and round-edged fridges. Although, while some of the garages had central heating. this I didn’t extend to the flats. There was also a tradesman’s entrance ‘in order to mitigate the noise and number of individual daily deliveries.

Other features of Stumperlowe include white wrought iron garden furniture and fox weather vanes, caravans and double garages, rhododendrons and pampas grass. holly- and ivy-covered walls. house names like The Gables, Birch Lodge, The Croft, Hawthorns- plus one or two Eldorado monstrosities. If you find yourself up there, look out for Manx gates, the wall with a quarry wheel embedded in it, the tree house and rope ladder. Oh, and the Stumperlowe Wives.

The first thing you notice is that it’s very quiet in this, one of the city’s most ancient districts. There’s muted bird song, the rustling of leaves, the whoosh of the odd squirrel leapfrogging over wrought iron gateposts, plus the purr of the occasional car. But there are very few people. Not on foot. anyway- Why should there be? There are no shops here, no community centre, no bus stops. no church – it’s halfway between St John’s. Ranmoor and Christ Church, Fulwood. Nothing. that is. to walk to. So the inhabitants either stay indoors behind the Austrian blinds, or glide out of their driveway in their indispensable cars.

The first thing you notice is that it’s very quiet in this, one of the city’s most ancient districts. There’s muted bird song, the rustling of leaves, the whoosh of the odd squirrel leapfrogging over wrought iron gateposts, plus the purr of the occasional car. But there are very few people. Not on foot. anyway- Why should there be? There are no shops here, no community centre, no bus stops. no church – it’s halfway between St John’s. Ranmoor and Christ Church, Fulwood. Nothing. that is. to walk to. So the inhabitants either stay indoors behind the Austrian blinds, or glide out of their driveway in their indispensable cars.

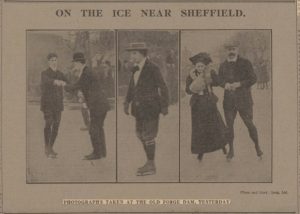

The skating was clearly organised and managed. At one point there is a gentleman in a dark suit and wearing a bowler hat. He is stationary in the middle of the ice and appears to be ensuring safety an suitabble behaviour. There are also men clearing away the loose ice created by the blades as the skaters twist and turn

The skating was clearly organised and managed. At one point there is a gentleman in a dark suit and wearing a bowler hat. He is stationary in the middle of the ice and appears to be ensuring safety an suitabble behaviour. There are also men clearing away the loose ice created by the blades as the skaters twist and turn