Charles Hanforth was born in 1894 and was baptised on 23rd December at St Mark’s Church on Glossop Road. His parents were Thomas and Alice Hanforth. Thomas had been born in Hunslett and at the age of 14 he was a chorister at York Minster. His family had moved to the city and were living at the Punch Bowl Inn on Stonegate where his father was the landlord.Ten years later Thomas was still with his parents but his occupation was described as a ‘performer of music,’ his father hving returned to his original craft of wheelwright.

Aged 25 years, Thomas was appointed organist at the Parish Church (now the Cathedral) in April 1892 and moved to Sheffield in June. This appointment enabled him to marry Alice Arrowsmith back in York 18 months later. In Sheffield, Thomas established himself as a teacher as well as organist becoming well known in the city.

Charles Hayden Hanforth

Charles Hayden and his brothers were all born in the family home on Shearwood Road but by 1901 the family had moved into a substantial house on Northumberland Road. From here Charles attended Western Road School before gaining a place at the Central Secondary School on Leopold Street and subsequently he was at King Edward VII School (KES). He gained a place at Keeble College College entering in Sepember 1913 where he was a member of the OTC just has he been in the OTC whilst at KES.

The family moved to Tom Lane about 1912 and after the war to 45 Clarendon Road.

Charles was one of the first to join up when war was declared. He was assigned to the 12th Service Battalion of the York and Lancaster Regiment as a private and eventually went to the camp at Redmires.

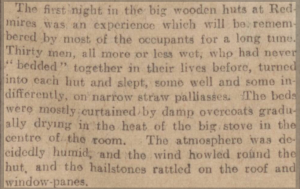

Extract from a report in the Sheffield Daily Telegraph 11th December 1914

Some idea of the training that Charles and the other recruits would have experienced is described here. When the Sheffield Pals Brigade moved into the hastily created camp in December 1914, the weather had been dreadful turning from rain in the city centre to sleet and snow at Redmires. Some of the huts which were like very large garden sheds were yet to be fitted with glazing.

Keith Barker, writing in ‘Tales from the Ridge’ says that “Living daily in a wooden hut on a cold, wet and windswept ridge some 1000 feet above sea level was never going to be a pleasant experience and some of the men suffered badly and the were were some deaths.

Charles Hanforth was one of those who succumbed to the conditions. As the Telegrph reported: “Just before Christmas he was taken ill with pneumonia and subsequently uderwent an operation at the Base Hospital. For time he appeared to be making an excellent recovery, but had relapse which ended fatally on Tuesday.” The report which was primarily about the funeral was printed on 12th February 1915, Hanforth’s death having occured on 9th February.

Hanforth Grave

The funeral was an extravagant affair at the Cathedral. This was because for the Battallion, this was the first death and the family was well connected. From the army, ‘A’ company of the Sheffield City Batallion provided 100 men to line the route (Sheffield City Battalion – Ralph Gibson & Paul Oldfield) or as the Telegraph reported they “formed up in two lines leading from the entrance gates in Church Street to the west door and thus kept the way clear for the mourners to proceed into the church.” The coffin was borne on a gun carriage to the Cathedral and by six of Hanforth’s comrades into the Cathedral. The Bishop and six clegymen leading the coffin all had some part in the service.

The coffin was then borne of the gun carriage along West Street and Glsoop Road, passing through Broomhill and along Fulwood Road to the churhyard at Fulwood. There were, not surprisingly, many lining the route.

A firing party and a bugular sounding the Last Post met the cortege at Fulwood, where Hanforth’s body was interred. The headstone bears the inscription

In loving memory of Charles Haydn, eldest son of

Thomas William & Alice Hanforth Keble College

Oxon, 12th Battn Y&L Regt. Died February 9th

1915 aged 20 years.

In due course, the grave would receive the bodies of both Thomas and Alice.

Alphaeus Casey, who was the same age as Hanforth and a student at Sheffield University, had joined at the same time. He kept a diary and commented on the preparations for the funeral. On 9th February, the day of Hanforth;’s death he wrote: “Heard Hanforth died having had relapse after operation in January. Neumonia[sic]” and noted that he had been selected as one of the firing party which involved learning how to march in slow time with rifles reversed (butt uppermost and muzzle canted downwards.)

Casey recorded the day of the funeral thus:

Hanforth’s funeral. Bearers left 10.45am. Platoon and other followers at 11.

Hurried dinner, Unwin rushing about, silly fool.

Bus to Crosspool, marched to Ranmoor Church, where, after waiting 1 ½ hrs, met procession from Cathedral.

Fell in with arms at reverse in front of gun carriage. Marched to Fulwood Churchyard at trail, changing arms, rifles reversed, last 150 yds slow march, arms reversed, very impressive. Opened out inside gate and rested on arms reversed after arm movement. Short cut to grave. Beautiful burial service by Chaplain. Present arms, 3 good volleys, fix bayonets, last tribute to dead present arms, last post. This was blown in splendid fashion and gave a grand and awe inspiring impression. Reminds one that a man yearns for a reawakening of the soul after death.

On the day after the funeral the Telegraph published an article that was probably written by the parent of a friend of Hanforth. The article provides some anecdotes about Hanforth and his plans for a future as a clergyman. There is a description of Hanforth character, “Although quite manly and rigorous he had very gentle manners and a sweet and attractive courtesy that made him an immediate favourite even with strangers.” the writer then finishes by reflecting on the ‘heavy toll of war.’ This is the article:

CURRENT TOPIC, YESTERDAY

we attended the funeral of Charles Hanforth, and witnessed the last honours paid to a singularly lovable and attractive personality. We had not seen anything of him during past year or so, but prior to that we came frequently into contact with him. He had inherited his father’s keen love of music and it so happened that he was one of small group of boys at King Edward School who interested themselves in the establishment of a School Orchestra, some of the rehearsals whereof were held at our house.

The difficulties were many and the encouragements marvellously few but Hanforth and his friends had the gift of persistence, and carried the thing through to at least one performance.

A School Orchestra.

“What do you think of it:” Charlie – as we called him then – asked us during interval in the practice. We searched our vocabulary for something complimentary, but Promising was the best we could do, for, to tell truth, it was not, as an orchestra, of much account. ” Ah. well,” he said. “we are going play if they laugh us off the platform” And play they did, with very fair success. We believe that under Dr. Duffell the School Orchestra has since assumed much more important proportions, but whatever it may do or be in the future, Hanforth and his six or seven enthusiastic friends were its pioneers

The Heavy Toll of War

On one occasion when we were discussing the question of careers and ideals, Hanforth told us that his ambitions lay toward Church, and we doubt whether we ever met a boy better fitted for the pulpit than he was. Although quite manly and rigorous he had very gentle manners and a sweet and attractive courtesy that made him an Immediate favourite even with strangers. And he possessed, too, a curious facility in, speech which promised well for his future congregations.

He was among the first to volunteer when the country’s call came to the nation’s young manhood, and he gave his life his country as truly as if he had fallen by a German bullet on some field of battle

That thought will be in some measure a consolation to his parents in their overwhelming load of sorrow. This war is taking a heavy toll of our youngest and best, and will exact a heavier one yet, but it will take no brighter or more hopeful or more promising life than that of the young man whom yesterday comrades of the Sheffield Battalion follow to his last resting-place.

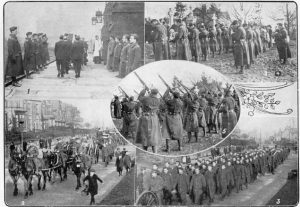

At the end of 1915, the Independent published a War Album ‘Our Boys at the Front’ that included this image of the funeral

1. Entering the Cathedral.

2 and 3. The cortege passing through Nether Green and members of the Battalion following.

4. At the graveside.

5. Last Salute.